The Cathedral and the Cloud

A Comparative Structural Analysis of Enterprise Computing Cycles (1960–1990) and the Artificial Intelligence Infrastructure Boom

Summary

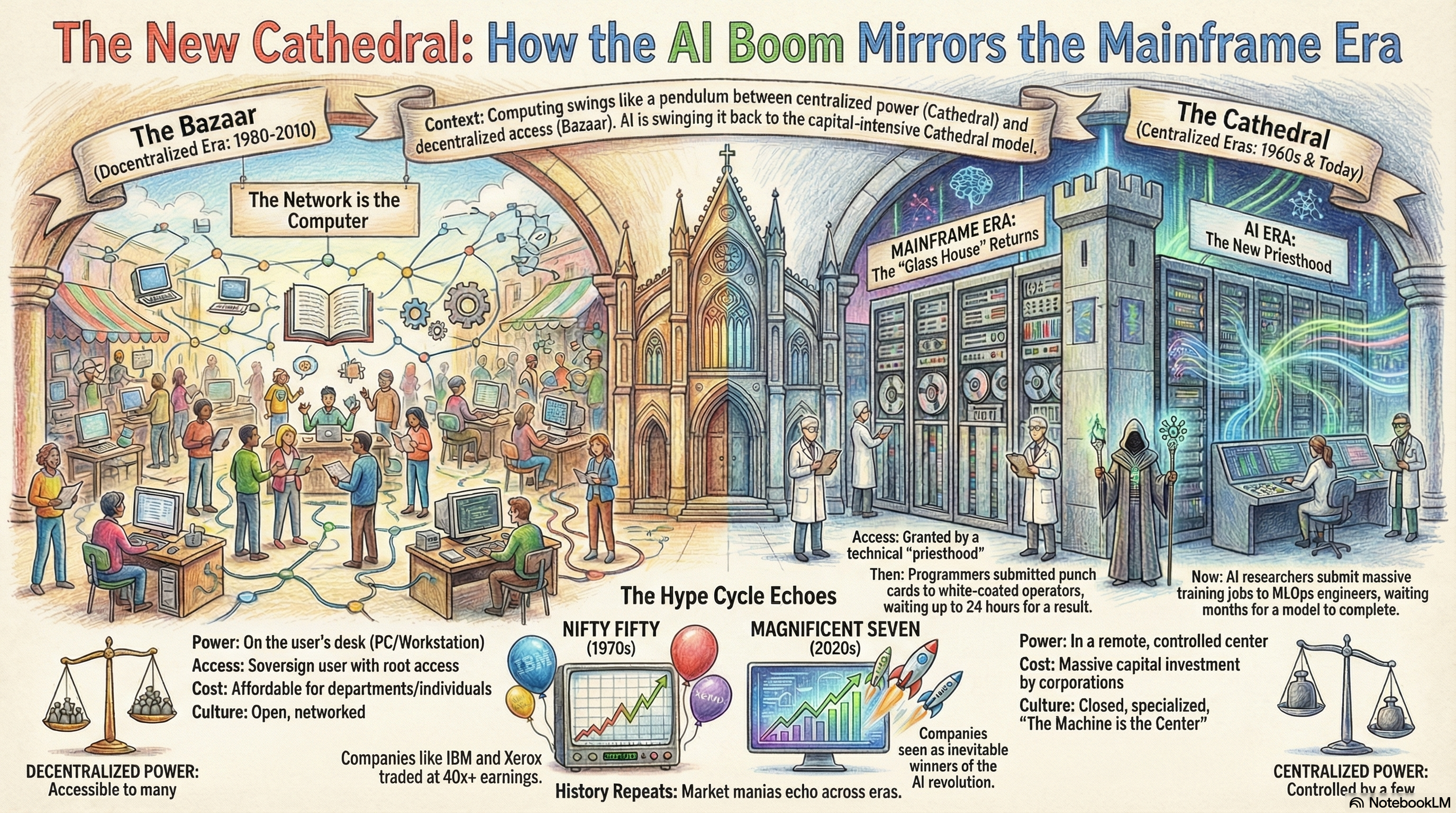

The history of enterprise computing is characterized not by linear progress, but by a pendular oscillation between centralization and decentralization, scarcity and abundance, and the physical manifestation of "the machine" versus its abstraction. This report provides an exhaustive comparative analysis of the foundational era of enterprise computing—spanning the mainframe dominance of IBM in the 1960s, the minicomputer revolution led by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in the 1970s, and the workstation era defined by Sun Microsystems in the 1980s—against the contemporary artificial intelligence infrastructure boom.

Through a rigorous examination of product architectures, human factors, and market psychology, this analysis argues that the current AI build-out represents a structural regression to the "Glass House" model of the 1960s. We are witnessing a return to massive capital intensity, specialized "priesthoods" of technical operators, and centralized control, albeit abstracted through the cloud. Furthermore, the analysis reveals striking parallels in public sentiment—specifically the "automation anxiety" of the 1960s versus modern AGI fears—and the economic behavior of "Nifty Fifty" style investment bubbles. The transition from the "Cathedral" of the mainframe to the "Bazaar" of the workstation is being reversed, as the economics of Large Language Models (LLMs) force a reconstruction of the Cathedral.

Part I: The Architecture of Heat and Iron (1964–1975)

1.1 The Definition of the Platform: System/360

The modern concept of enterprise infrastructure was codified on April 7, 1964, with IBM’s announcement of the System/360. Prior to this inflection point, the computing landscape was fractured into incompatible silos; a customer upgrading from a small IBM 1401 (business) to a larger 7090 (scientific) faced the insurmountable friction of rewriting software entirely.1 The System/360 was a USD 5 billion gamble—roughly twice IBM’s annual revenue at the time—predicated on the revolutionary concept of a unified architecture.1

The System/360 introduced the platform business model to computing, separating software from hardware and allowing the same binary executable to run on a processor costing thousands or one costing millions.1 This architectural unification allowed for the consolidation of scientific and commercial computing, formerly distinct domains, into a single "data processing" hegemony.2

Comparative Insight: The Unified Model

In the current AI boom, we observe a homologous drive toward unified architectures. However, the unifying layer has shifted from the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) to the software-hardware interface, specifically NVIDIA’s CUDA stack. Just as the System/360 allowed a unified approach to "data processing," modern AI infrastructure unifies "inference and training" across scalable clusters. The risk profile mirrors the 1960s; the massive capital expenditures (CAPEX) required for modern GPU clusters—where hyperscalers invest tens of billions annually—echo the "bet the company" magnitude of IBM's 1960s investment, which IBM President Tom Watson Jr. famously called "the biggest, riskiest decision I ever made".3

1.2 The "Glass House" and the Thermodynamics of Intelligence

The physical manifestation of enterprise computing in the 1960s was the "Glass House." Computers were not invisible utilities; they were massive, physical installations designed for conspicuous consumption. Corporate data centers were constructed with glass walls, allowing the public to view the spectacle of spinning tape drives and flashing lights, while strictly barring entry to the uninitiated.4 This design choice balanced conflicting requirements: the need for hermetic environmental stability and the desire to project corporate status.4

The defining constraint of the Glass House was thermodynamics, a constraint that has returned with vengeance in the AI era. As mainframes grew in power, air cooling became insufficient. By the 1980s, high-performance mainframes like the IBM 3081 and 3090 utilized Thermal Conduction Modules (TCMs)—complex, helium-filled, water-cooled pistons—to manage heat fluxes that had risen from 0.3 W/cm² in the System/360 era to 3.7 W/cm².5

| Specification | IBM Mainframe Era (e.g., IBM 3090/ES9000) | Modern AI Cluster (e.g., NVIDIA H100/Blackwell) |

|---|---|---|

| Cooling Method | Water-cooled TCMs & Chillers 5 | Direct-to-Chip Liquid Cooling / Rear-door Heat Exchangers |

| Heat Flux | ~3.7 - 11.8 W/cm² 5 | >100 W/cm² (Modern GPUs) |

| Power Density | ~100 kW per rack (Blue Gene/Q) 6 | >100 kW per rack (NVL72 Blackwell racks) |

| Physical Manifestation | "Glass House" Display 4 | Hyperscale Data Center (Opaque, Remote) |

| Environmental Req. | Strict humidity/temp control (40-60% RH) 7 | Strict liquid flow rates and filtration |

The parallel is exact: The transition from air-cooled server racks to liquid-cooled AI clusters mirrors the mainframe’s evolution from the air-cooled System/360 to the water-cooled 3090. Just as IBM engineers wrestled with plumbing and flow rates to sustain the "intelligence" of the 1980s enterprise, modern data center architects are redesigning facilities for the hydraulic requirements of generative AI. The "Glass House" has returned, though now it is hidden in rural Virginia or Oregon rather than displayed in a Manhattan lobby.

Part II: The Priesthood and the Batch Queue (The Human Factor)

2.1 The Sensory Experience of the Mainframe Era

To understand the "daily experience" of the 1960s and 70s, one must reconstruct the sensory environment of the data center, which was visceral and tactile.

- Olfactory: The machine room had a distinct, sharp smell of ozone generated by high-voltage printers and electronics, often commingled with the stale smoke of cigarettes, as operators were frequently permitted to smoke at the console.8

- Auditory: The environment was deafening. The white noise of massive air conditioning units competed with the rhythmic clatter of line printers and the vacuum-column whoosh of tape drives.4

- Tactile: Computing was heavy. Programmers physically carried their logic in the form of "decks" of 80-column punch cards. A box of 2,000 cards weighed roughly 10 pounds; dropping a deck was a catastrophe that could require hours of manual resorting.9

2.2 The Ritual of Batch Processing

The dominant operational mode was "batch processing," which enforced a high-latency feedback loop that culturally defined the era.

- Coding as Manual Labor: Programmers wrote code by hand on coding sheets. These were handed to keypunch operators—often women, reflecting the era's gendered division of labor—who transcribed the marks into holes.10

- The Submission: The programmer submitted the deck through a window to the "computer operator," a specialized technician in a white lab coat. The operator was the gatekeeper; the programmer was the supplicant.4

- The Wait: The job entered a physical queue. Turnaround time could be 24 hours or more.

- The Verdict: The output appeared in a pigeonhole the next day, usually as a stack of green-bar fanfold paper. A single syntax error meant the entire process had to be repeated.10

This latency created a culture of the "Computer Priesthood." The scarcity of compute cycles meant that access was a privilege. It forced a discipline of "desk checking" or "mental compiling," where programmers would simulate the machine's logic in their heads for hours to avoid the cost of a failed run.10

Comparative Insight: The Return of the Batch Job

While modern inference is instantaneous, the creation of AI models has returned to the high-latency batch processing of the mainframe era. Training a Large Language Model (LLM) is a massive batch job that runs for months. If the run fails or the loss curve diverges, millions of dollars and weeks of time are lost. The "AI Researcher" designing the run is the new programmer submitting a deck; the "DevOps/MLOps" engineers managing the cluster are the new white-coated operators; and the GPU cluster is the new mainframe—scarce, expensive, and temperamental.

Part III: The Minicomputer Rebellion and Corporate Cultures (1975–1990)

3.1 DEC and the Democratization of Compute

If the mainframe was the Cathedral, the minicomputer was the Reformation. Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), led by Ken Olsen, introduced machines like the PDP-8 and the VAX-11/780 that were small enough and cheap enough for individual departments to own.11

- The Cultural Shift: This broke the monopoly of the central computing center. A physics lab could buy a VAX and run it themselves. This fostered a culture of interactivity. Unlike the batch-oriented mainframe, the VAX used time-sharing to allow users to interact directly with the machine via terminals.

- The VUP Standard: The VAX-11/780 became the industry standard unit of measurement—the "VAX Unit of Performance" (VUP). A computer was rated by how many VUPs it could deliver, a precursor to today's obsession with FLOPs and parameter counts.12

3.2 Route 128 vs. Silicon Valley: A Study in Industrial Sociology

The computing build-out was geographically bifurcated between Route 128 (Boston) and Silicon Valley (California). Their divergent cultures offer critical lessons for the current AI landscape.

The Route 128 Model (DEC, Wang, Data General):

- Vertical Integration: Companies were autarkic. DEC built everything: the chips, the disk drives, the OS (VMS), and the networking (DECnet).

- Hierarchy: The culture was formal ("suits"), risk-averse, and demanded loyalty. Information sharing between companies was viewed as leakage. This was the "Company Man" era.13

- The Failure Mode: This insularity proved fatal. By refusing to embrace open standards (Unix) and commodity hardware until it was too late, Route 128 companies were dismantled by the horizontal, modular ecosystem of the West Coast.14

The Silicon Valley Model (Sun Microsystems, HP):

- Horizontal Integration: Sun Microsystems, founded in 1982, epitomized this. They used standard Unix (BSD), standard networking (Ethernet/TCP/IP), and standard microprocessors (initially Motorola, then SPARC).15

- Networked Culture: High labor mobility ("job-hopping") was a feature, not a bug. It allowed for rapid cross-pollination of ideas. Failure was tolerated, and equity compensation aligned workers with high-risk outcomes.13

- "The Network is the Computer": Sun’s slogan presaged the cloud. They realized that the value was not in the box, but in the connection between boxes.15

Implications for AI

The current AI landscape is split between the "Route 128" style closed labs (OpenAI, Google DeepMind) which keep weights and architectures proprietary, and the "Silicon Valley" style open ecosystem (Meta LLaMA, Hugging Face, Mistral). History suggests that while the vertical integrators (IBM/DEC) dominate early revenue, the horizontal, open ecosystem eventually commoditizes the stack.

Part IV: The Workstation and the Specialized Hardware Trap

4.1 Sun Microsystems and the Rise of the Sovereign User

By the mid-1980s, the "Glass House" had been breached. The Sun Workstation (e.g., the SPARCstation "pizza box") placed the power of a VAX directly on the user's desk.16

- Experience: The user was no longer a supplicant to an operator. They were sovereign. They had root access. The feedback loop tightened from days (mainframe) to milliseconds (workstation).

- The Unix Wars: This era saw brutal competition between Unix vendors (Sun, HP, IBM) to define the standard interface. This fragmentation (the "Unix Wars") eventually opened the door for Microsoft NT and later Linux to unify the market.17

4.2 Symbolics and the Lisp Machine: A Cautionary Tale

An often-overlooked parallel to today’s NVIDIA dominance is the Lisp Machine boom of the 1980s. Companies like Symbolics designed specialized hardware to run Lisp, the primary language of AI at the time.18

- The Architecture: These machines used 36-bit tagged architectures to handle AI-specific tasks (garbage collection, dynamic typing) in hardware, offering performance general CPUs could not match.19

- The Demise: Symbolics machines were technically superior but economically doomed. The "Killer Micro" (standard CPUs from Intel/Sun) advanced in speed so rapidly that they could eventually emulate Lisp in software faster than Symbolics could build custom hardware. The specialized "AI chip" was crushed by the volume economics of the general-purpose chip.20

Current Parallel

This threatens the current wave of specialized AI inference chips (ASICs/LPUs). If general-purpose GPUs (or even CPUs) continue to improve via Moore’s Law and volume economics, highly specialized AI hardware may face the same extinction event as the Lisp Machine.

Part V: The Economics of Hype and Public Sentiment

5.1 The Nifty Fifty and Valuation Manias

The financial backdrop of the enterprise computing build-out was the "Nifty Fifty" bubble of the early 1970s. Institutional investors flocked to 50 "one-decision" stocks—companies viewed as so dominant and high-quality that they could be bought at any price.

- The Players: The list was dominated by the tech giants of the day: IBM, Xerox, Polaroid, DEC, Burroughs.21

- The Valuations: In 1972, the P/E ratio of the Nifty Fifty averaged 42x, more than double the S&P 500. Polaroid traded at a staggering 90x earnings.22

- The Crash: The 1973–74 bear market decimated these valuations. Xerox fell 71%, IBM fell 73%, and Polaroid dropped 91%.23

Economic Parallel

The current concentration of market gains in the "Magnificent Seven" (NVIDIA, Microsoft, etc.) mirrors the Nifty Fifty dynamics. The sentiment that these companies are "immune to economic cycles" because AI is inevitable 21 is a recurring psychological pattern. The Nifty Fifty proves that a company can be a monopoly and technologically vital (like IBM) and still be a disastrous investment if purchased at a peak of hysteria.

5.2 Automation Anxiety: The Triple Revolution

Public sentiment in the 1960s regarding computers was dominated by "Automation Anxiety," strikingly similar to today's AGI fears.

- The Triple Revolution: In 1964, a group of Nobel laureates and activists sent a memo to President LBJ warning that "cybernation" (automation + computing) would break the link between income and employment, creating a permanent underclass.24

- The Media Narrative: Time magazine and labor leaders warned of a "jobless future" where machines would replace not just muscle, but mind.25

- The Outcome: The 1960s saw low unemployment. The technology shifted labor from manufacturing to services rather than eliminating it.26 Today's AGI discourse, predicting the end of white-collar work, is a beat-for-beat reprise of the 1964 panic, likely to resolve in a similar transformation rather than cessation of labor.

5.3 The Myth of the Paperless Office

The 1975 prediction of the "Paperless Office" 27 serves as a critical lesson in second-order effects.

- The Prediction: A 1975 BusinessWeek article predicted that by 1990, office automation would eliminate paper.28

- The Reality: Paper consumption doubled between 1980 and 2000.27

- The Mechanism: Computers (and laser printers) lowered the cost of generating paper documents to near zero. When the cost of production drops, volume explodes.

AI Implications

We predict AI will reduce the need for software developers and content creators. History suggests AI will lower the cost of code and content generation to near zero, leading to an explosion in volume. The bottleneck will shift to verification, curation, and integration, increasing the value of human judgment just as the printer increased the volume of paper.

Part VI: Synthesis and Conclusion

6.1 The Return to the Cathedral

The most profound insight from this analysis is that the current AI boom represents a reversal of the 50-year trend toward decentralization.

- Decentralization Cycle (1975–2010): Computing power moved from the Center (Mainframe) to the Edge (Minicomputer -> PC -> Smartphone).

- Re-Centralization Cycle (2010–Present): Computing power is collapsing back into the Center (Cloud -> Hyperscale AI Cluster).

The H100 GPU cluster is the new Mainframe. It is too expensive for individuals to own (USD 25,000+ per unit). It resides in a "Glass House" (the cloud data center) managed by a new "Priesthood" (AI Researchers/ML Ops). The users interact via "terminals" (browsers) but have lost the sovereignty of the workstation era. We have returned to the era of Big Iron, where the machine is the master of the center.

6.2 CAPEX Super-Cycles

In the 1960s, IT capital expenditure was a massive percentage of corporate budgets, often justified by vague promises of future efficiency.29 We are in a similar CAPEX super-cycle. Companies are spending billions on infrastructure (NVIDIA chips, data centers) based on FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out) and projected rather than actualized revenue.30 The "Nifty Fifty" crash warns us that when the infrastructure build-out outpaces the utility of the applications, a violent correction is inevitable.

Final Word

The enterprise computing build-out of the 1960s–1980s laid the physical and cultural foundation of the digital age. While the technology has evolved from vacuum tubes to transformers, the sociology of computing remains remarkably consistent. The "Glass House" has been rebuilt, the "Priesthood" has been re-ordained, and the "Paperless Office" paradox reminds us that technology rarely subtracts work—it only changes its nature. The transition from the IBM Mainframe to the Sun Workstation was a journey from the Cathedral to the Bazaar. The modern AI boom is the reconstruction of the Cathedral—larger, faster, and more powerful than ever, but fundamentally a return to the centralized, capital-intensive model of the past.

References

-

The IBM System/360, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/history/system-360 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

IBM System/360 - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IBM_System/360 ↩

-

The 360 Revolution - IBM z/VM, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.vm.ibm.com/history/360rev.pdf ↩

-

Room with a VDU: The Development of the 'Glass House' in the Corporate Workplace - Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive, accessed December 7, 2025, https://shura.shu.ac.uk/7971/1/Room_with_a_VDU_shura.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

Exploring Innovative Cooling Solutions for IBM's Super Computing Systems: A Collaborative Trail Blazing Experience - Clemson University, accessed December 7, 2025, https://people.computing.clemson.edu/~mark/ExploringInnovativeCoolingSolutions.pdf ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

IBM System Blue Gene/Q, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.fz-juelich.de/en/jsc/downloads/juqueen/bgqibmdatasheet/@@download/file ↩

-

Overview - IBM NeXtScale System with Water Cool Technology, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/overview-ibm-nextscale-system-water-cool-technology ↩

-

What do you remember most about the very first time you used a computer? - Reddit, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/AskOldPeople/comments/14o88fz/what_do_you_remember_most_about_the_very_first/ ↩

-

What was mainframe programming like in the 60s and 70s? : r/vintagecomputing - Reddit, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/vintagecomputing/comments/1pctkkd/what_was_mainframe_programming_like_in_the_60s/ ↩

-

How was working as a programmer in the 70s different from today? - Quora, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.quora.com/How-was-working-as-a-programmer-in-the-70s-different-from-today ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

VAX-11 – Knowledge and References - Taylor & Francis, accessed December 7, 2025, https://taylorandfrancis.com/knowledge/Engineering_and_technology/Computer_science/VAX-11/ ↩

-

VAX-11 - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VAX-11 ↩

-

How Silicon Valley Became Silicon Valley (And Why Boston Came In Second) - Brian Manning, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.briancmanning.com/blog/2019/4/7/how-silicon-valley-became-silicon-valley ↩ ↩2

-

BOOK NOTE REGIONAL ADVANTAGE: CUL'ITIRE AND COMPETITION IN SILICON VALLEY AND ROUTE 128 - Harvard Journal of Law & Technology, accessed December 7, 2025, https://jolt.law.harvard.edu/articles/pdf/v08/08HarvJLTech521.pdf ↩

-

Sun Microsystems - Grokipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://grokipedia.com/page/Sun_Microsystems ↩ ↩2

-

Sun SPARCStation IPX - The Centre for Computing History, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.computinghistory.org.uk/det/26763/Sun-SPARCStation-IPX/ ↩

-

Unix wars - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_wars ↩

-

Symbolics - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symbolics ↩

-

Symbolics Technical Summary - Symbolics Lisp Machine Museum, accessed December 7, 2025, https://smbx.org/symbolics-technical-summary/ ↩

-

Symbolics, Inc.:, accessed December 7, 2025, https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/6-933j-the-structure-of-engineering-revolutions-fall-2001/30eb0d06f5903c7a4256d397a92f6628_Symbolics.pdf ↩

-

America's Nifty Fifty Stock Market Boom and Bust, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.thebubblebubble.com/nifty-fifty/ ↩ ↩2

-

LESSONS FROM THE PAST: WHAT THE NIFTY FIFTY AND THE DOT.COM BUBBLES TAUGHT US, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.bordertocoast.org.uk/news-insights/lessons-from-the-past-what-the-nifty-fifty-and-the-dot-com-bubbles-taught-us/ ↩

-

Occasional Daily Thoughts: Bubbles and Manias in Stock Markets - LRG Wealth Advisors, accessed December 7, 2025, https://lrgwealthadvisors.hightoweradvisors.com/blogs/insights/occasional-daily-thoughts-bubbles-and-manias-in-stock-markets ↩

-

The Triple Revolution - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Triple_Revolution ↩

-

The Story of MLK and 1960s Concerns About Automation - American Enterprise Institute, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.aei.org/articles/the-story-of-mlk-and-1960s-concerns-about-automation/ ↩

-

Job Automation in the 1960s: A Discourse Ahead of its Time (And for Our Time), accessed December 7, 2025, https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1874&context=faculty_publications ↩

-

Paperless office - Wikipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paperless_office ↩ ↩2

-

Paperless office - Grokipedia, accessed December 7, 2025, https://grokipedia.com/page/Paperless_office ↩

-

The Growth of Government Expenditure over the Past 150 Years (Chapter 1) - Public Spending and the Role of the State, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/public-spending-and-the-role-of-the-state/growth-of-government-expenditure-over-the-past-150-years/2D56740AECACE5774DF6AE8128646685 ↩

-

2022 Capital Spending Report: U.S. Capital Spending Patterns 2011-2020, accessed December 7, 2025, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/econ/2021-csr.html ↩